My essay “Ireland’s First Sacred Harp Convention: ‘To Meet To Part No More'” was published in the journal Southern Spaces a few months ago. The subject of the piece is the first Ireland Convention, which was held in Cork, Ireland, last March. Now that the second Ireland Convention is just a few days away (it will be held March 3–4), I thought I would post some further reflections on last year’s event and my experience writing about it.

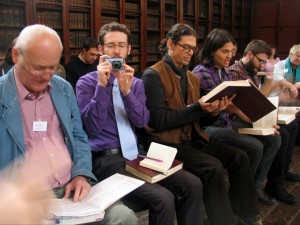

In my essay I situate the first Ireland Convention in the context of the establishment of Sacred Harp conventions outside the southeastern United States over the past four decades and describe how the Cork convention (like the New England Convention and other relatively new conventions) was founded thanks to influences from academic and traditional channels, was a revelatory emotional experiences for many who attended, and precipitated reciprocal travel among new groups of singers. As is the case with all of my research on Sacred Harp singing, writing and researching this essay was a moving experience.

My fieldwork for this article took me not just to Ireland, but to new digital spaces where Sacred Harp singers from across Europe and the United States are meeting and conversing about their singing experiences. In the wake of the Ireland Convention Irish, English, Polish, and American Sacred Harp singers took to Facebook to effuse about the Cork convention. I cited several of these comments in my essay, but in the wake of the convention my Facebook wall and the Cork Sacred Harp Facebook page overflowed with moving reflections.

Now, a year after the convention, Facebook groups continue to loom large in my research. Posts on the Sacred Harp Singers of Cork and Sacred Harp in Poland pages leave traces of the strengthening connections between singers from these places and newer groups in Germany and elsewhere in Ireland. These Facebook groups are sites of negotiation where singers try to fit their own understandings of religious faith, community activity, and music with the body of traditions associated with Sacred Harp singing for which they themselves feel compelled to advocate. Just as the National Sacred Harp Newsletter in the 1980s and 1990s, and the Fasola listservs in the 1990s and 2000s, facilitated the expansion of Sacred Harp singing across the United States, ((See John Bealle, Public Worship, Private Faith: Sacred Harp and American Folksong (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997) and Kiri Miller, Traveling Home: Sacred Harp Singing and American Pluralism (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008) for extended treatments of the roles the Newsletter and the Fasola listserv played in the recent expansion of Sacred Harp singing across the United States.)) Facebook has become the tool of choice for facilitating the spread of Sacred Harp across Europe in the 2010s.

The fieldnotes I took in preparation for writing my Southern Spaces essay include my reflections on the singing school and singing sessions themselves and the time I spent with other singers in pubs around Cork. They quote conversations I had with singers in these spaces as well as on Facebook and Google chat in the wake of the convention. My tone is impassive at the start of the singing. I focus on describing the event with a clear eye toward any perceived divergences from traditional practice, or any emblems of a Cork singing style. As the singing continues, however, the tenor of my fieldnotes shifts as I become engrossed in the revalatory experience Alice Maggio described in her post-convention blog post. ((See also Alice Maggio, “Wesleyan Sacred Harpers around the world,” WesLive (blog), March 31, 2011, http://community.blogs.wesleyan.edu/2011/03/31/wesleyan-sacred-harpers-around-the-world/ and Alice Maggio, “First Irish Sacred Harp Convention,” The Trumpet 1 (2): vi, June 2011.)) I write of my critical faculties being lost, and of feeling genuinely overwhelmed with love for my new singing friends.

In my fieldnotes I am revealed as an ethnographer but also as a participant. I express the same feelings of love and connection to new singing friends that singers expressed on Facebook and at the pubs at which we lingered until late in the night on Sunday, hoping to delay the conclusion of the weekend for another hour. In Traveling Home: Sacred Harp Singing and American Pluralism Kiri Miller writes of how all Sacred Harp singers behave like ethnographers to a certain extent. ((Miller, Traveling Home.)) Certainly since the first secretary of a Sacred Harp convention recorded minutes singers have attempted to preserve a record of their gatherings. In the first half of the twentieth century Sacred Harp singers such as J.S. James and Earl Thurman attempted to document the early history of The Sacred Harp. ((See J. S. James, A Brief History of the Sacred Harp and Its Author, B. F. White, Sr., and Contributors (Douglasville, GA: New South Book and Job Print, 1904) and, on the first century of the Chattahoochee Musical Convention, Earl Thurman, “The Chattahoochee Musical Convention, 1852–1952,” in The Chattahoochee Musical Convention, 1852–2002: A Sacred Harp Historical Sourcebook, edited by Kiri Miller, 29–120 (Bremen, GA: The Sacred Harp Museum, 2002).)) From the 1960s through the present numerous singers have brought portable recording devices to singings in an attempt to capture what they experienced. Singers have related to these documents both as overwhelmed lovers of Sacred Harp singing and as scholars, attempting to account for their experiences and understand their importance. As a researcher thoroughly committed to my participation in the Sacred Harp singing tradition I attempt to understand and situate, this dual desire can sometimes feel distorting and dangerous. Yet at other moments, as during the research and writing of “To Meet To Part No More,” the tension between these two modes can enrich my experience, enjoyment, and understanding.