I’m excited to announce that Sounding Spirit, a project I direct at the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship, received a $260,000 grant today from the National Endowment for the Humanities through the Scholarly Editions and Translations program. The three-year grant will support the publication of five digital critical editions of important songbooks from the southern vernacular sacred music diaspora—collections of spirituals, shape-note music, hymns, and gospel. This funding will help boost our capacity and enable us to hire a managing editor for the project.

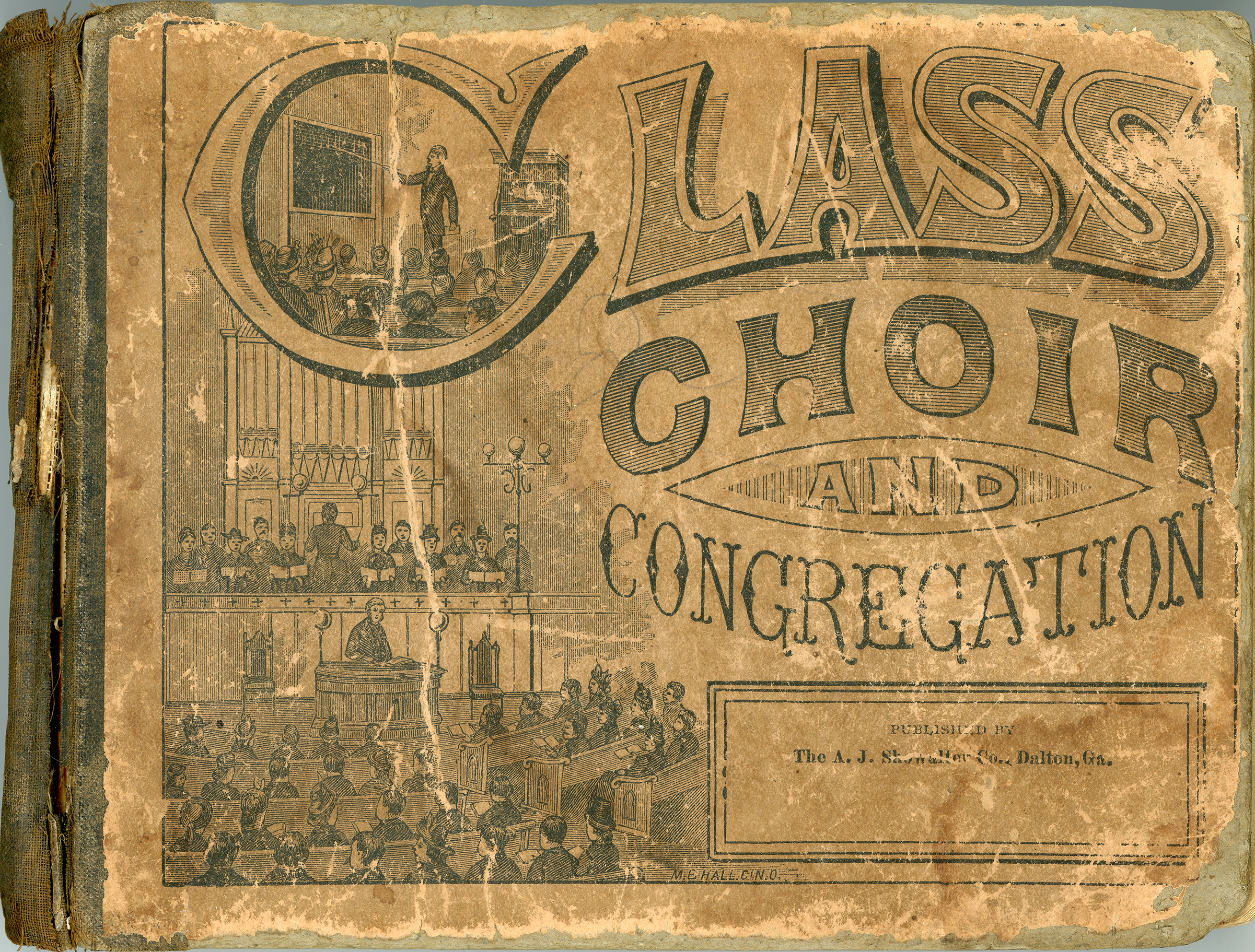

As described on the Sounding Spirit project site, the initiative focuses on songbooks in these genres between 1850 and 1925,

a time of great dramatic demographic and cultural change that shaped intersections of race, religion, region, and music in the United States. These genres refracted these issues and comprise the roots of popular music in the twentieth century. These songbooks, part of the Pitts Theology Library English and American Hymnody and Psalmody Collection, are drawn from different religious groups, include the work of black, white, and Native American contributors, and each represent music using different music notation and book designs, shedding light on the relationship of music forms to identity.

The digital and print editions will be co-published by ECDS and the University of North Carolina Press in a first-of-its-kind open access publishing partnership. Several ECDS staff members will support this work, including my former advisor, Allen Tullos, who serves as the project co-director. Sara Palmer, Jay Varner, Yang Li, and Robert A. W. Dunn will also contribute expertise.

Sounding Spirit complements existing music edition projects. The Committee on the Publication of American Music recognized that Sounding Spirit covers “highly significant vernacular American musical repertoire … ground that has been overlooked by complementary publication projects, including COPAM’s own flagship series,” Music of the United States of America (MUSA). Happily, MUSA, co-edited by Sounding Spirit editorial board member Mark Clague, also received funding today through the NEH’s Scholarly Editions and Translations program. Together, the awards comprise a remarkable showing of support for scholarly editing in American music.

Another project of mine was also approved for funding today through the NEH’s Digital Humanities Advancement Grants program. The Digital Drawer, a project to develop and test a platform for crowd-sourcing rural history was approved for $86,471 of level 2 funding. I serve as co-director of this project, which is directed by Scott Robertson of Georgia Institute for Technology’s Interactive Media Technology Center in partnership with ECDS and Historic Rural Churches of Georgia.

I’m humbled and gratified by this outstanding support for these initiatives at the intersection of digital humanities, critical regional studies, and preservation. And I’m particularly thankful to the US legislators and their constituents who have fought to preserve the vital federal funding for the humanities that makes work like this possible.

This September I will be transitioning into an exciting new role at Emory University that mixes my interests in collaborative digital research projects, nineteenth- and twentieth-century American music, teaching, and interdisciplinary editing and publishing about the southern United States. After a year as postdoctoral fellow in digital humanities publishing, I will be joining the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship full time as senior digital scholarship strategist.

This September I will be transitioning into an exciting new role at Emory University that mixes my interests in collaborative digital research projects, nineteenth- and twentieth-century American music, teaching, and interdisciplinary editing and publishing about the southern United States. After a year as postdoctoral fellow in digital humanities publishing, I will be joining the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship full time as senior digital scholarship strategist.