This fall I’m presenting internationally on Sacred Harp singings geography, history, racial politics, and contemporary relationship to the past. I’m also speaking on Southern Spaces’s newly redesigned Drupal-based website and on Readux, Emory’s new platform for reading and annotating digitized books and publishing digital critical editions.

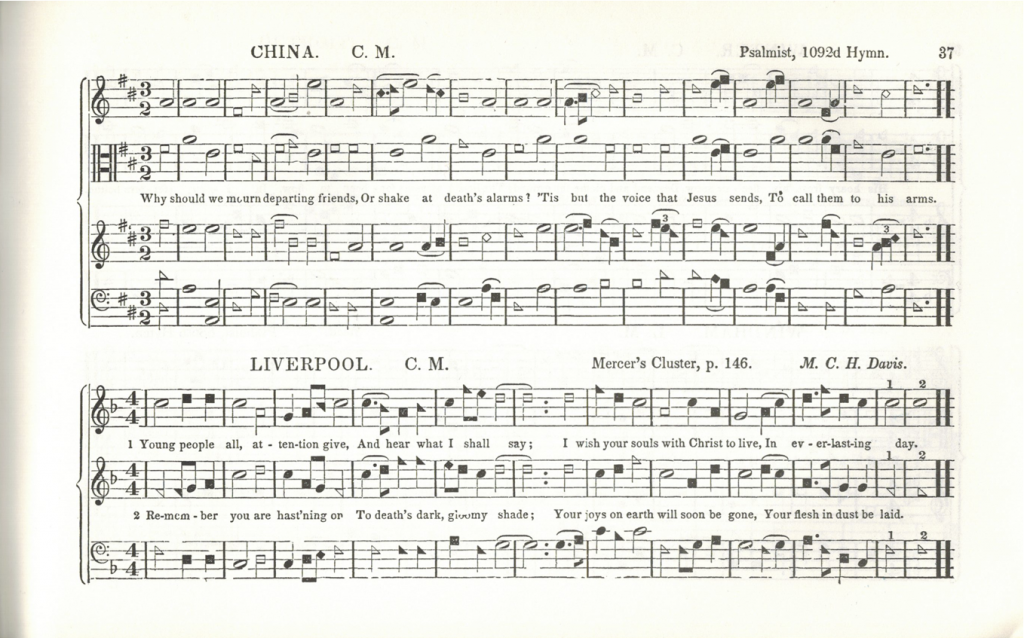

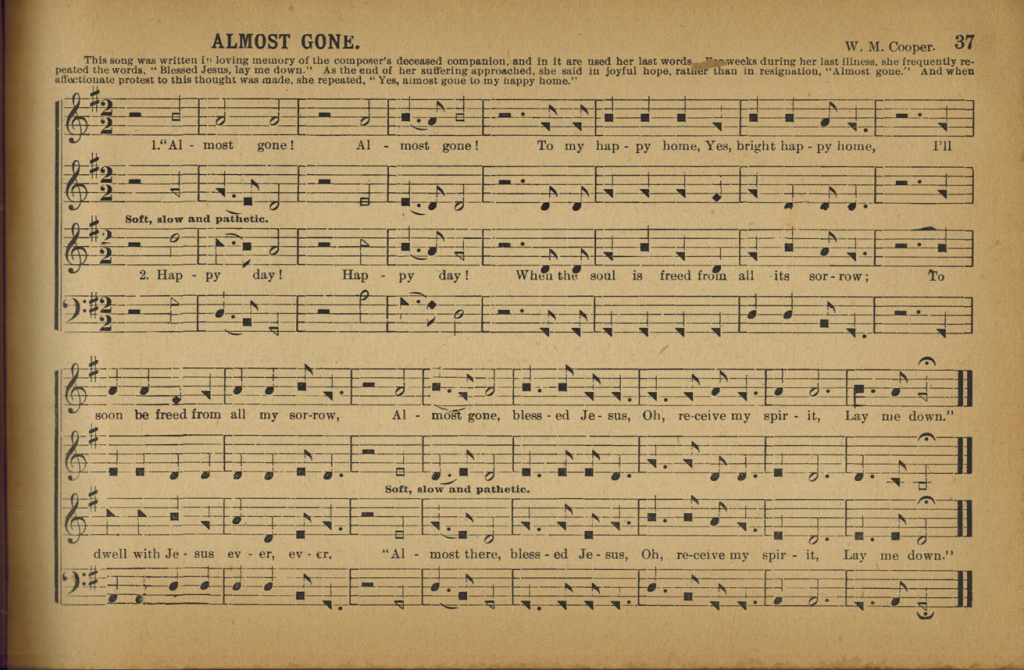

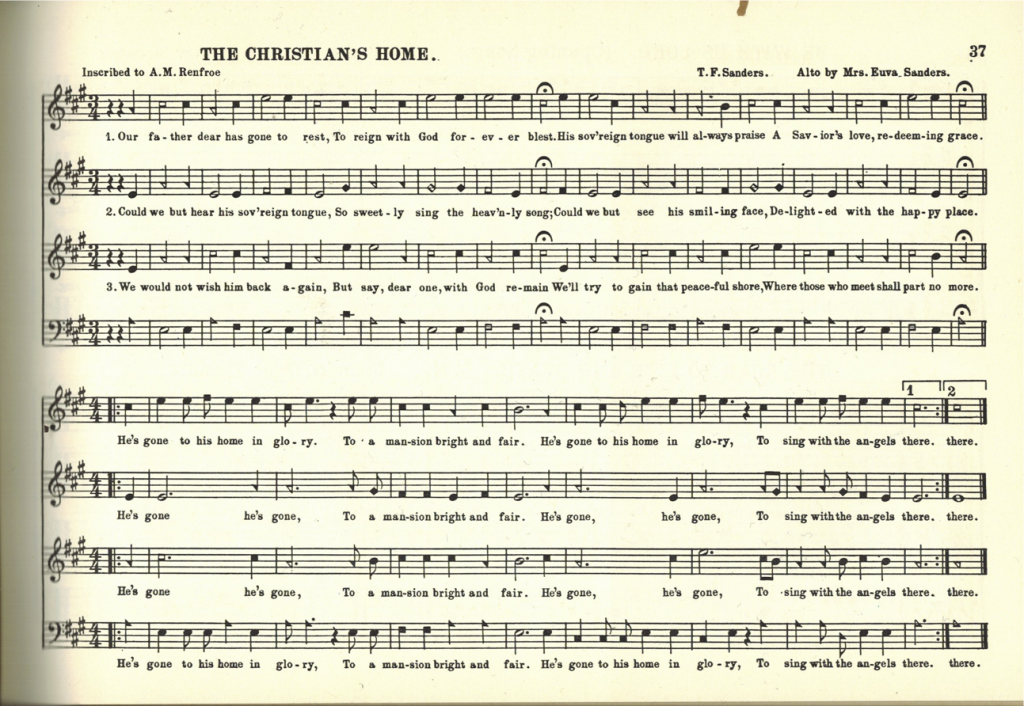

In late August I traveled to Utrecht, in the Netherlands, to give a pair of presentations on Sacred Harp’s history and the relationship of contemporary singers to that past. My talk “Resonance and Reinvention: Sounding Historical Practice in Sacred Harp’s Global Twenty-First Century” at the Stichting voor Muziekhistorische Uitvoeringspraktijk [Foundation for Historical Musical Performance Practice] described frames of folk and early music applied to Sacred Harp singing have affected contemporary singers’ and performing ensembles’ conceptions of the style’s aesthetics. This symposium is held each year in conjunction with the Festival Oudemuziek Utrecht, a large international early music festival. The festival this year featured a Sacred Harp singing school taught by Cath Tyler of Newcastle, United Kingdom, and an all-day singing, the first in the Netherlands. In addition to participating in the singing, I gave a short talk on Sacred Harp’s history and geography to complement Cath’s singing school.

In October and November I’ll give two additional talks on Sacred Harp’s history, here centered on interactions between folklorists and Sacred Harp singers in the field and at folk festivals. In “Separate but Equal?: Civil Rights on Stage at Sacred Harp Folk Festival Performances, 1964–1970” at the American Studies Association in Toronto, Canada, part of a session I organized on “Race and Resistance in the Folklorization and Reappropriation of Musical Cultures of Struggle,” I’ll describe how folk festival organizers drew on ideas about the civil rights and folk music movements when deciding how to program Sacred Harp singers at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival and the 1970 Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife, and will speak about how these concerns differed from singers’ own priorities. Later, at the Alabama Folklife Association’s Fall into Folklife symposium, I’ll speak about Alan Lomax’s relationship to Sacred Harp singing, focusing on the recordings that emerged from his visit to 1959 United Sacred Harp Musical Association in Fyffe, Alabama, and the encounter’s influence on Sacred Harp singing ever since.

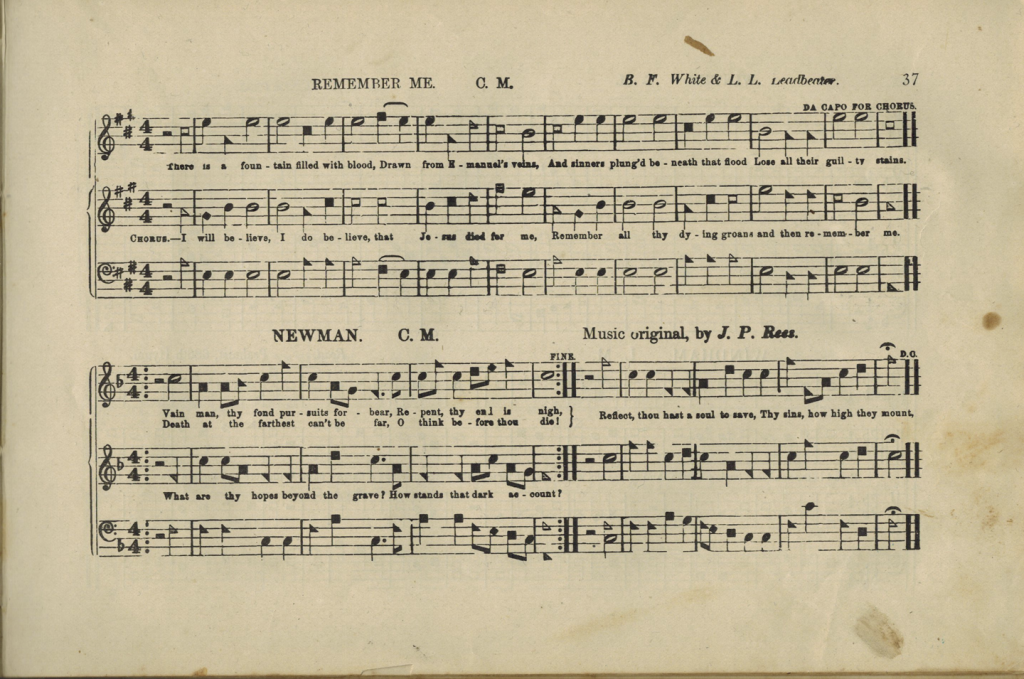

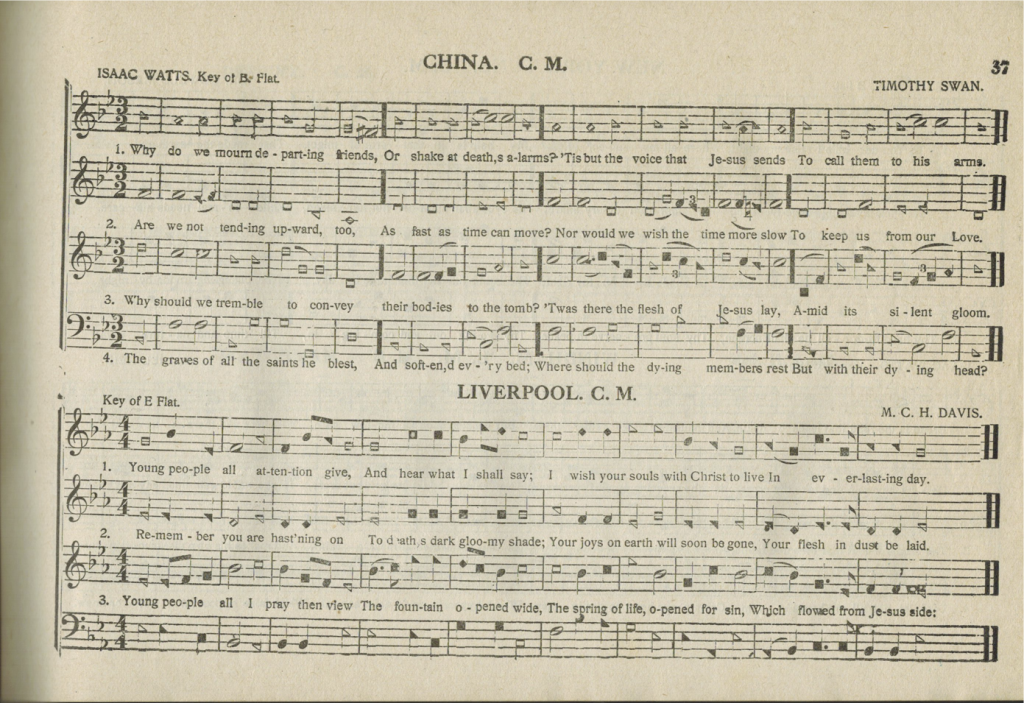

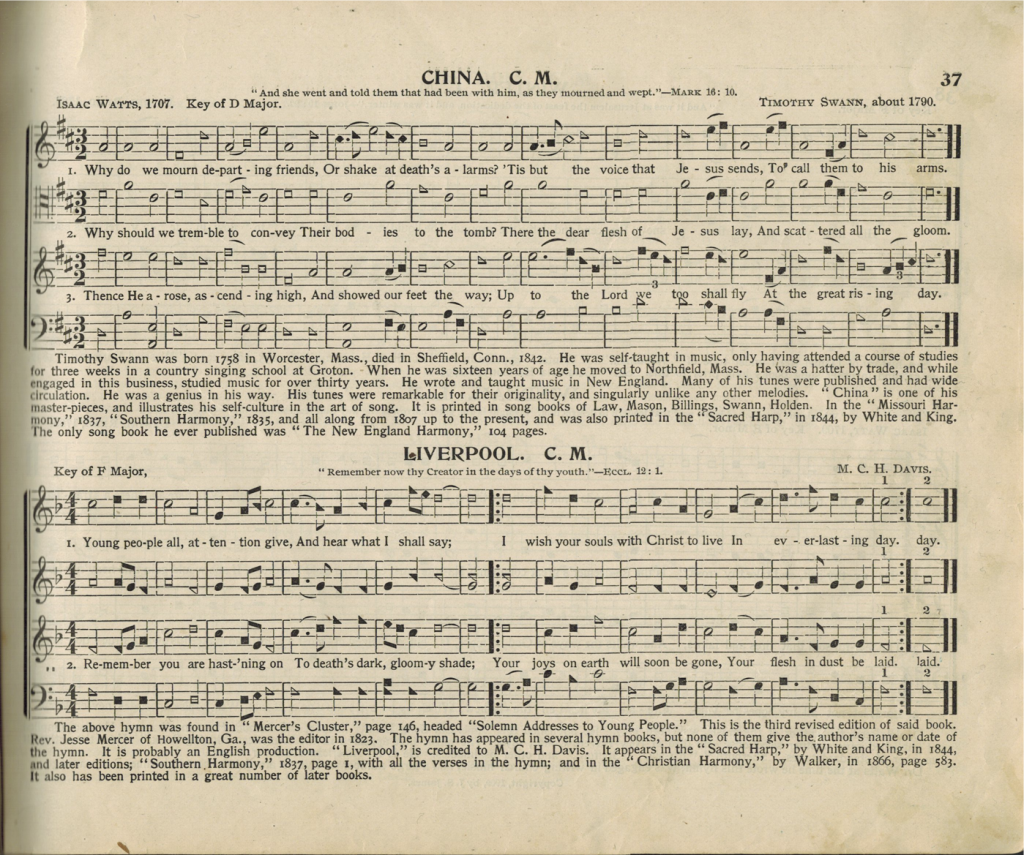

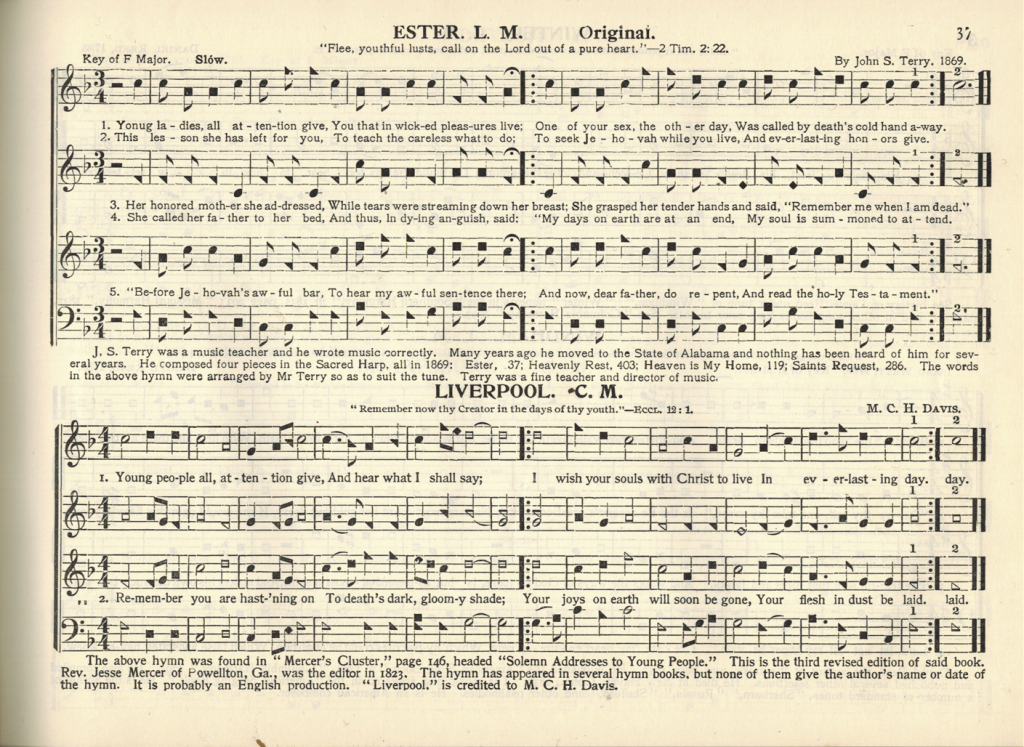

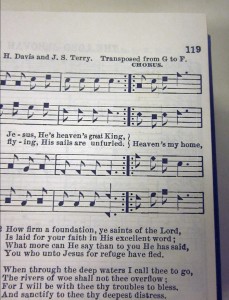

One final talk on Sacred Harp singing, at the American Academy of Religion meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, illuminates a little-told chapter of Sacred Harp’s racial history. In “The Black in ‘White Spirituals,'” I detail the racial politics and musical landscape of the nineteenth-century West Georgia setting in which the Sacred Harp’s compilers lived and worked. I argue that revival choruses, the song form most characteristic of the editions of The Sacred Harp edited in this region, emerged from the mixed-race religious context of early nineteenth century camp meetings, and may have reached the ears of Sacred Harp contributors sung by enslaved African Americans.

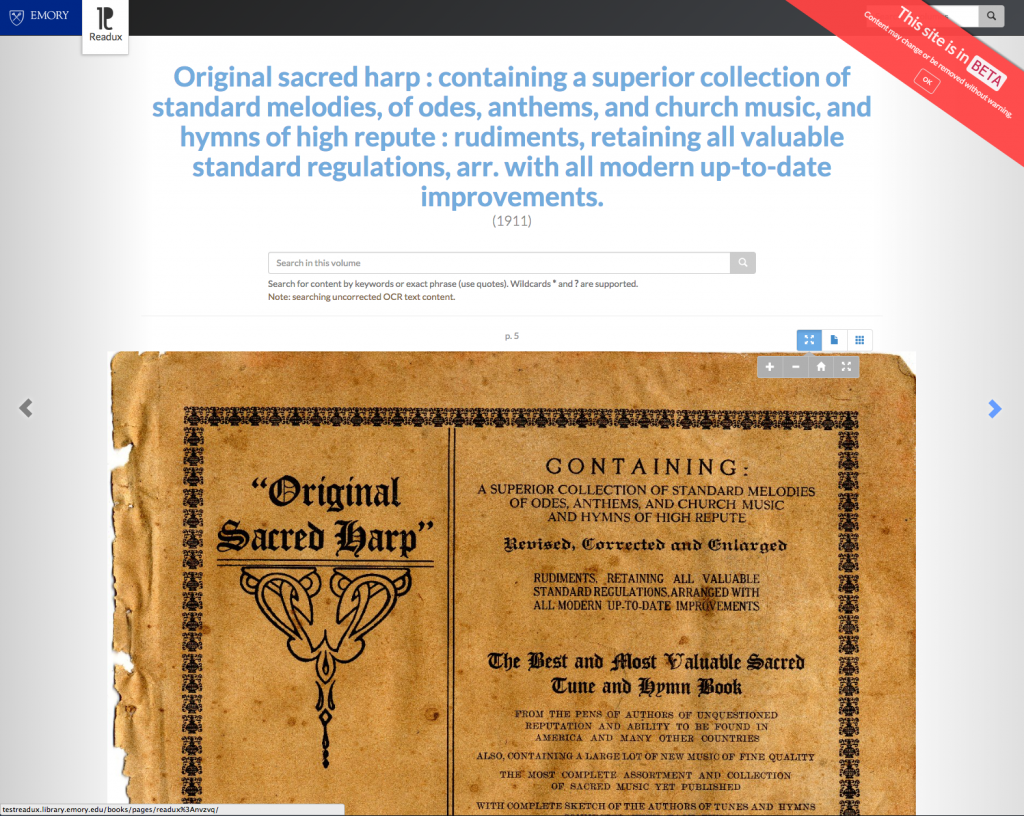

I’ll also give three presentations this fall on new digital platforms I’ve helped develop for open access journal and scholarly edition publishing. In presentations at the Digital Library Federation in Vancouver, Canada (with Sarah Melton), and at Drupalcamp Atlanta (with Daniel Hansen), I’ll detail the Drupal 7–based platform for scholarly journal publishing developed for Southern Spaces in conjunction with Sevaa Group, Inc., a project I oversaw as the journal’s managing editor. I’ll also speak at Emory University’s Currents in Research lecture series on the Readux platform’s value for editing and publishing annotated facsimile digital scholarly editions.

![Black southeastern Alabama singer "Dewey [Williams] must get his own gas" at a service station outside Ozark, Alabama, June 1968. Photograph and notes by William H. Tallmadge. Courtesy of Berea Sound Archives.](http://jpkarlsberg.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Screen-Shot-2014-08-06-at-3.35.25-PM-300x173.png)