In a new article, “Genre Spanning in the Close and Dispersed Harmony Shape-Note Songs of Sidney Whitfield Denson and Orin Adolphus Parris,” in the latest issue of American Music I argue that often-reified boundaries between dispersed harmony and convention gospel were porous and frequently crossed by mid-twentieth-century Alabama composers. I focus on compositions by Sidney “Whit” Whitfield Denson (1890–1964) and Orin Adolphus “O. A.” Parris (1897–1966), two singer-composer-compilers from northern Alabama. In the essay,

I argue that Denson and Parris tailored their contributions to fit the genre conventions of the oblong tunebooks and gospel convention songbooks in which their music appeared while also infusing much of their work with hybrid harmonic and lyrical language and extending elements from one shape-note genre to another. Their composition and songbook editing practices reveal a musical culture in which a variety of shape-note genres coexisted, influenced one another, and attracted overlapping followings.

In pointing to these composers’ genre-crossing work, my article challenges assumptions about the stylistic boundaries of white gospel music and Sacred Harp singing. My article also contributes to “the discussion of genre classification, development, boundary work, and disruption,” suggesting that boundary-spanning can actually contribute to the reification of genres.

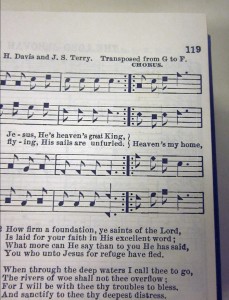

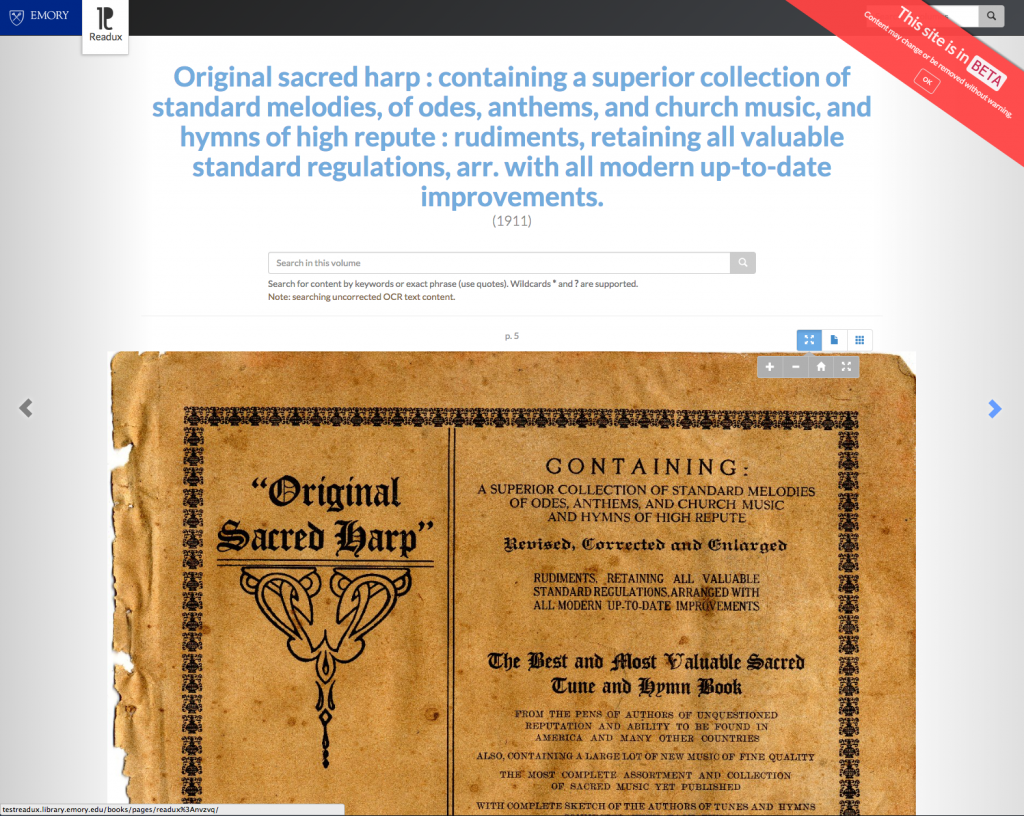

In addition to making these contributions, I also hope that the article’s concise treatment of topics such as dispersed harmony and categories of contrapuntal effects in gospel music, will prove useful to others. A section of the article delves into the notation systems, harmonic styles, text meters, and contrapuntal effects in different shape-note genres, along with a review of scholarship on these topics.

I also contributed an essay summarizing and expanding upon my argument to the latest issue of the Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter. In “Orin Adolphus Parris: At Home Across the Shape-Note Music Spectrum,” I detail O. A. Parris’s “unique and masterful approach to crafting new tunes in … three shape-note styles”: Sacred Harp, Christian Harmony, and gospel. This essay afforded me an opportunity to comment more extensively on Parris’s virtuosic approach to composition, noting favorite harmony parts (“the bass in ‘Eternal Praise’ and the treble to ‘A Happy Meeting,'” both in The Christian Harmony), and articulating how “Parris’s harmony parts …elegantly interact with each other both rhythmically and melodically, like pieces of a puzzle snapping together.” As I note in the Newsletter, Parris and Denson were just two members of a group “that included several Densons, Kitchenses, McGraws, and Woodards” in the mid-twentieth century who applied their creativity across the shape-note genre spectrum.

But among this group, Parris seemed perhaps the most at home in the widest range of genres, capable in songs like “The Better Land” and “The Grand Highway” of mixing and matching elements from different styles while creating music that feels just right in its intended source.

Many thanks to all those who read and commented on drafts of these two essays, and to the archivists who assisted me in accessing the often obscure gospel publications featuring songs by these composers. Thanks, especially, to the descendants of Whit Denson and O. A. Parris, who shared family photographs and granted me permission to reprint their talented relatives’ songs.