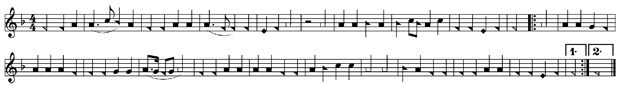

“Perhaps the most instantly recognizable musical feature of” Sarah Lancaster’s song “The Last Words of Copernicus” (p. 112 in The Sacred Harp) “was not in [the composer’s] original three-part setting,” I wrote in the winter 2013–2014 issue of the Country Dance and Song Society News. I continued:

The alto entrance to the song’s fuging section features a simple figure located at the moment in the song where the two highest parts drop out, leaving the altos singing exposed, with relish, at the top of their range. ((Jesse P. Karlsberg, “Imagining ‘The Last Words of Copernicus,’” Country Dance and Song Society News (Winter 2013–2014): 19, http://www.cdss.org/tl_files/cdss/newsletter_archives/news/CDSS_News_winter_2013-2014_song_copernicus.pdf.))

Used by permission.

This alto entrance in The Sacred Harp, 1991 Edition and its predecessors shines through on recordings of “The Last Words of Copernicus,” and even caught the ear of a producer of Bruce Springsteen’s single “Death to My Hometown,” from the 2012 album Wrecking Ball. ((An identical alto part has appeared in the various editions of Original Sacred Harp published between 1911 and 1987. Bruce Springsteen, Wrecking Ball, Columbia, March 6, 2012.)) As I noted in the CDSS News, the producer sampled this portion of the tune’s Original Sacred Harp alto part and included it in a musical interlude that recurs throughout Springsteen’s song. ((Karlsberg, “Imagining ‘The Last Words of Copernicus,'” 19. See also Jesse P. Karlsberg and John Plunkett, “Bruce Springsteen’s Sacred Harp Sample,” Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 1, no. 1 (March 28, 2012), http://originalsacredharp.com/2012/03/28/sightings-bruce-springsteens-sacred-harp-sample/.))

Clearly integral to the song’s contemporary appeal, the alto line to “The Last Words of Copernicus” is uncredited in the 1911 Original Sacred Harp in which it first appeared in its present-day form.

Who wrote it?

Three Early Twentieth-Century Alto Parts

Joseph Stephen James, and his colleagues on the five-member “sub-committee on revision” that edited Original Sacred Harp, credit Seaborn McDaniel Denson with 327 “altos composed … and added [in] 1911” in the book’s “Summary Statement.” ((Joseph Stephen James et al., “Summary Statement,” in Joseph Stephen James et al., eds., Original Sacred Harp (Atlanta, GA: United Sacred Harp Musical Association, 1911).)) The book’s editors explicitly list Denson as alto author on many songs’ pages, but a number of additional alto parts, though uncredited, may represent his work as well. For this reason, Warren Steel suggests that “The Last Words of Copernicus” alto part, as it appeared in Original Sacred Harp, is “probably by S. M. Denson.” ((David Warren Steel with Richard Hulan, Makers of the Sacred Harp (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 194.))

As Steel and others have shown, however, many of the alto parts Denson added to Original Sacred Harp were his arrangements or selections of alto parts published in earlier works. In particular, Denson often drew on the alto parts included in Wilson Marion Cooper’s 1902 revision of The Sacred Harp (commonly known as the “Cooper book”), and William Walker’s 1866 The Christian Harmony.

Lancaster’s “The Last Words of Copernicus” does appear, with an alto part by “Miss Minnie Floyd” (a prolific writer of alto parts) in the 1902 “Cooper book.” The song is also included, with an uncredited alto, in the “remodeled and improved” second half of James Landrum White’s 1909 The Sacred Harp: Fifth Edition, the first of three attempts by this son of Sacred Harp co-compiler Benjamin Franklin White to revise the tunebook. ((W. M. Cooper, ed., The Sacred Harp (Dothan, AL: W. M. Cooper, 1902), 112; J. L, White, ed., The Sacred Harp (Atlanta, GA: J.L. White, 1909), part 2, 112. Thanks to John Plunkett and Sarah Kahre for reminding me of these two pre-1911 publications including four-part versions of “The Last Words of Copernicus”.))

How Do the Alto Parts Line Up?

While J. L. White’s 1909 alto part and Minnie Floyd’s 1902 parts have significant differences, close comparison reveals that over 60 percent of their notes are identical. ((Though the author of the alto part that appears in J. L. White’s The Sacred Harp: Fifth Edition is uncredited, I describe the part as White’s in this post both for the sake of simplicity and because White takes credit elsewhere for “remodeling” the book’s songs. In making this comparison I’ve ignored other changes White made to Lancaster’s song such as lowering the key from F major to E flat major; replacing pairs of half notes with dotted half notes and quarter notes; and replacing the half note, half rest, and half note at the midpoint of the plain section with two quarter notes whose durations are extended by holds.))

Blue notes are identical to the notes Floyd wrote for the “Cooper book.” Black notes are original to White’s version.

Some of these forty-seven matches seem likely to be coincidental. In other places, though, such as measures four through seven in the middle of the plain section (four through six in White’s version), and fifteen through eighteen toward the middle of the fuging section (fourteen through seventeen in White’s version), the similarities are striking, last for multiple measures, and feature unusual musical figures. It seems overwhelmingly likely, then, that White had access to a copy of Cooper’s Sacred Harp revision, and drew on Minnie Floyd’s alto part for “The Last Words of Copernicus” in fashioning his own alto part.

Among White’s deviations from Floyd is the addition of a catchy flourish at the start of the song’s fuging section. This quarter note 5-sol, three 3-la quarter notes, and second 5-sol quarter note comprises the first publication of the recognizable figure from “The Last Words of Copernicus” noted above (though to be fair White’s version is in a different key, and starts with a quarter note, rather than half note, pickup). Aside from this addition, White’s changes generally seem aimed to lower the part’s range. ((White decreased the time the alto part spends in the upper part of the alto range by replacing 5-sol and 4-fa notes with lower notes in a few cases. He seems to have been particularly concerned with replacing instances of the 4-fa notes with 1-fa or 3-la notes, perhaps creating more conventional chord voicings while also lowering the part. In measure fourteen (thirteen in White’s version), White removed a flourish from Floyd’s part and added a quarter note enabling the altos to sing the entire Doddridge hymn text.))

Seaborn McDaniel Denson’s alto part for the 1911 Original Sacred Harp, though presented as an addition to the three-part version of the song added to The Sacred Harp in 1870, appears to draw on both alto parts that preceded it in print.

Blue notes are identical to the “Cooper book” version, red notes are identical to the “White book” version, and purple notes are the same in all three alto parts. Black notes are original to Denson’s version.

Only eight notes in Denson’s alto part differ from both Floyd’s and White’s alto lines. In a couple of other measures Denson’s part is original as well. ((In the song’s first measure, and its ninth, for example, its contour is sufficiently distinct that the instances where individual notes are identical to those in one or both of the two other alto parts are likely incidental.)) Just about everywhere else, however, Denson’s part largely follows Floyd’s, or White’s or both.

While White’s changes lowered the alto’s range, Denson’s shift the part higher. Denson seems to have selected the higher of the two available figures from Floyd or White with few exceptions. And three of the eight notes original to Denson’s parts replace the lowest note in the other two alto parts (the 7-mi) with a higher note (the 2-sol). In including high 5-sol notes but avoiding notes below the bottom space in the G clef, these changes are consistent with other alto parts in F major that Denson contributed to James’s Original Sacred Harp.

Comparing all three parts suggests that Denson likely used both Floyd’s and White’s alto parts as models. For much of the part’s plain section (measures three through eight), Denson follows Floyd almost exactly, copying note for note the unusual figure in measures seven through eight where the part soars upwards. Yet for much of the song’s fuging section, Denson’s alto imitates White’s, particularly at the start of the fuge (measures ten through twelve) and from the song’s alto treble duet nearly to its end (measures fifteen through twenty). ((For parts of each of these three sections of the song all three alto parts are the same. (See, for example, measures three, fifteen, sixteen, and twenty.) Identifying the presence of notes I’ve marked red and the absence of those marked blue around and between purple notes (or vice versa), however, is a strong indication that Denson’s model in that place was Floyd’s part (or White’s, in the case of red notes and not blue).)) While Denson may not have composed much of the Original Sacred Harp alto part for “The Last Words of Copernicus,” he does seem to have intentionally selected from the two previously composed alto parts available to him in putting the part together.

The Last Word

Who, then, composed the alto part to “The Last Words of Copernicus” that appears in The Sacred Harp, 1991 Edition?

S. M. Denson likely stitched together pieces of the two previously published alto parts by Minnie Floyd and J. L. White, making alterations or substituting his own inventions as he saw fit. Perhaps Minnie Floyd can take credit for portions of the plain section, though its final few notes owe more to J. L. White. White’s alto part seems to have been the model for the song’s fuging section, including the much loved entrance, though White’s fuging section cribbed extensively from Floyd’s. ((Twenty-seven of the notes in Denson’s fuging section are shared by all three parts, and many should thus be credited to Floyd.)) The alto entrance that Springsteen sampled is most effective in Denson’s version, which retains Sarah Lancaster’s half note pickup, lengthening the high 5-sol at the start of the fuge.

In assessing Denson’s methods for adding alto parts to songs in Original Sacred Harp we might add to the three strategies already well documented,

- composing the alto part himself,

- copying the alto part, unchanged, from an earlier source, or

- arranging the alto part from an earlier source, with minor—or major—modifications,

a fourth strategy,

- piecing the alto part together from two or more earlier sources.

Should we credit Denson as the probable composer of the alto part? Our answer may tell us more about our contemporary understanding of the word “composer” than it reveals about Denson’s activities or motivations. ((Thanks to Warren Steel for helpful comments on how to describe Denson’s work assembling the alto part for “The Last Words of Copernicus.”))

A better approach might be to continue to document the range of strategies Denson employed in devising 327 alto parts during the rush to bring Original Sacred Harp to publication between 1910 and 1911. How many other alto parts in the book (if any), did Denson stitch together in this manner? Are there alto parts where Denson stitched more of his own original writing together with music from one or more precursors?