This spring I’m presenting on a range of topics on the cultural politics and book history of Sacred Harp singing in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The topics range from the Philadelphia print culture that produced the meticulously composed Sacred Harp editions of the 1840s–1860s to 1960s black South Alabama singers’ disagreements over the politics of protest.

In February I presented a paper co-written with Christopher Sawula at the Auburn University Montgomery Southern Studies conference on the life and music of Philadelphia bookkeeper Elphrey Heritage. Our paper argues that many of the songs Heritage contributed to tunebooks like The Christian Minstrel, The Hesperian Harp, The Social Harp, and The Sacred Harp, show musical markers of close and dispersed harmony styles. Combined with evidence of social interaction between Heritage, his employer the printer Tillinghast King Collins, and tunebook compilers William Hauser and John G. McCurry, Heritage’s music offers a glimpse into a Philadelphia social scene in the 1840s and 1850s that affected the form of southern shape-note tunebooks to a greater extent than commonly acknowledged.

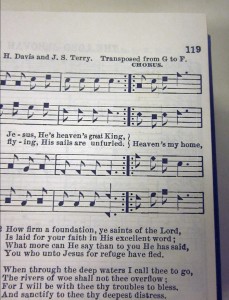

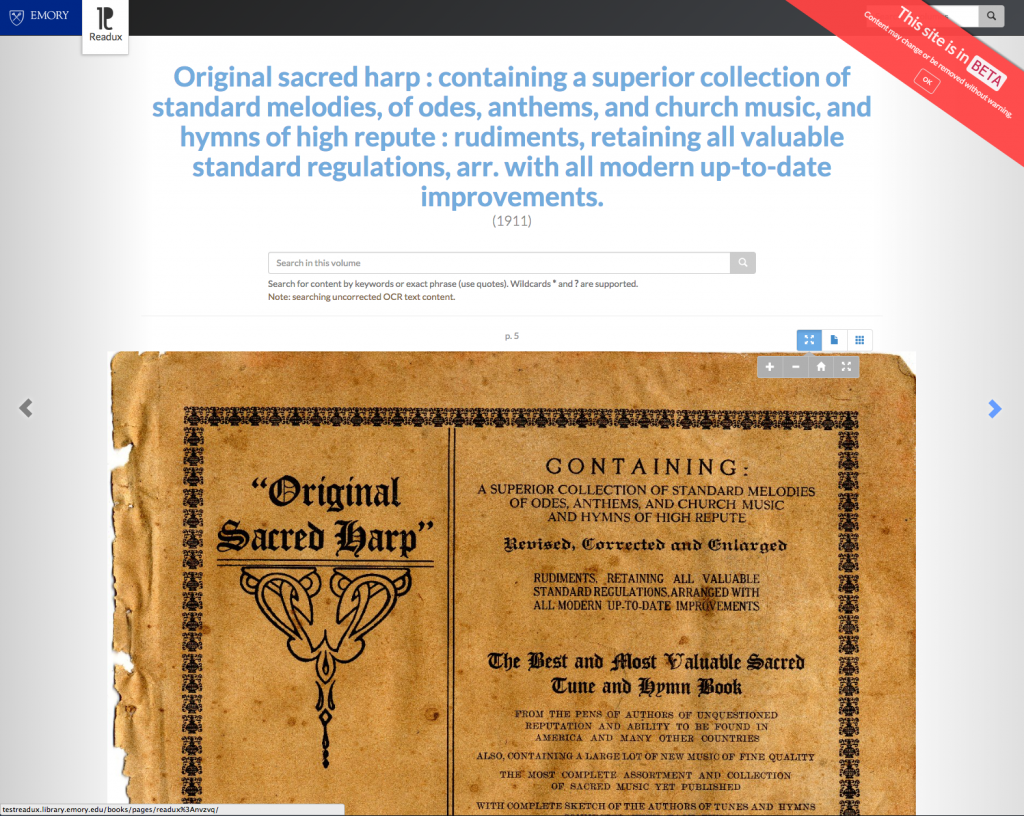

The next weekend I presented a lecture–participatory singing at Emory during a joint session of the Society for Christian Scholarship in Music and the Emory Sacred Harp singing focusing on the musical conservatism and material modernity of Joseph Stephen James’s Original Sacred Harp. My talk, which also served as the official launch of the new Original Sacred Harp: Centennial Edition, was a hands on tour of the book’s design and contents, articulating how its various features illuminated its revisers’ aims and social context. After a short break over 100 singers and conference attendees joined in singing a range of songs from the new edition illustrating its editors’ musical choices. Amy Kiley, a reporter from Atlanta’s NPR station, WABE, covered the event and the publication of my new edition.

I presented at another conference in Atlanta the following weekend, the Southern American Studies Association, on the politics of race and protest that emerged in a 1968 field recording in which SUNY Buffalo music professor William H. Tallmadge interviews south Alabama reverend Shem Jackson, a son of Colored Sacred Harp compiler Judge Jackson. During an interview largely about services and singings at Jackson’s church the conversation unexpectedly turns to Jackson’s resistance to his daughter Mary’s participation in student protest at Tuskegee Institute—protests which Tallmadge seems to regard positively. I presented this paper as part of a panel on race and Sacred Harp singing, where I was joined by Nathan Rees, who spoke about the Wiregrass singers’ album cover art, and Jonathon Smith, who discussed celtic imagery in representations of East Tennessee New Harp of Columbia singers. Douglas Harrison, an insightful scholar of southern gospel, chaired our session.

Earlier this month I presented a paper on how Texas singers associate the layout of pre–digitally retypeset Sacred Harp editions with the sound of small rural singings and find both an impediment to efforts promoting the style to urban(e) southern audiences. My paper, delivered at the annual meeting of the Society of American Music in Sacramento, drew on Buell Cobb‘s metaphor of “the South’s ring of repugnance” to describe how such singers invest the digital with the potential to erase the vernacular rusticity that some newer singers romanticize, echoing a folkloric paradigm.

Later this month I will travel to Boston for the Nineteenth Century Studies Association, where I will speak about the nineteenth century editions of The Sacred Harp. Far from a vernacular folk production, The Sacred Harp was a meticulously produced publication of T. K. and P. G. Collins, a high status firm at the center of the emerging national book trade.

I’ll travel from Boston to Portland, Oregon, to present one final paper, discussing the Readux platform under development at the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship at the Library Publishing Forum. Readux is a new tool for reading, annotating, and publishing digital critical editions of digitized texts. The open source platform is designed to foreground scanned page images, paired with fully searchable text and robust multimedia annotations mapped to page regions. A digital critical edition of Original Sacred Harp will serve as a proof of concept demonstration of the tool’s capacity and will be the first in a series of editions featuring nineteenth- and twentieth-century sacred tunebooks and manuscripts, but the platform will also be available for use, for free of charge, by others interested in editing and publishing digital critical editions.